On December 23, 1924, a team of renowned international businessmen met in Geneva, and this gathering would transform the lighting industry for decades that followed.

The meeting comprised of four representatives from the leading manufacturers of lightbulb:

- Philips (Netherlands)

- Compagnie des Lampes (France)

- General Electric (United States)

- Osram (Germany)

As revelers hung various Christmas lights across the city, this team founded the Phoebus cartel, a body that would determine the direction of the incandescent lightbulb market in the world.

The cartel assigned production quotas and manufacturers to each regional and national zone. Historically, it was the first cartel that enjoyed a historical reach.

A Shorter Lifespan for a Lightbulb

The cartel’s control on the lightbulb market could only last into the 1930s. By 1925, it had established 1000 hours limit for a lightbulb, which was a drop from the standard limit of 1,500 to 2,000 hours.

According to cartel members, this strategy was a trade-off: the lightbulbs with the 1000 hours limit were more efficient, of better quality, and brighter compared to other bulbs. Besides, their bulbs cost more.

Instead of designing a product that could meet the needs of consumers, the cartel’s motivation was to manufacture and sell a lightbulb that would bring in more sales and profits.

By carefully making a lightbulb with a shorter life span, the Phoebus cartel hatched an industrial plan that’s commonly known as planned obsolescence.

Most countries now prefer the pricier and energy-efficient LEDs to incandescent lighting. Thus, it’s important to revisit this history – not merely as a quirky story from the tech archives, but rather as a cautionary look at the unexpected and bizarre pitfalls that could emerge when new technologies replace old ones.

The Challenges of Running a Lightbulb Company in the 1920s

Being a lightbulb maker in the twentieth century was challenging. The fast spread of electrification, as well as the new lighting methods, such as streetlights, car headlights, and bicycle lamps, presented incredible opportunities for entrepreneurs and investors.

However, as many manufacturers rivaled for a share of the market and technological advancement, it was difficult for most companies to be guaranteed stable revenue each year. This applied to both small companies and large organizations with international factories and research firms.

For example, following the formation of the Phoebus cartel, Osram experienced a drastic fall in German sales. The drop was from 63 million in the 1922/1923 financial year to 28 million a year later.

Unsurprisingly, William Meinhardt (Osram head) was the first person to give a suggestion that later on turned into the Phoebus cartel.

Other Powerful Alliances in the Lightbulb Industry (But No Match to Phoebus Cartel)

It was common for lightbulb manufacturers to form alliances. For example, the Verkaufsstelle Vereinigter Glühlampenfabriken – a European cartel of carbon filament lamp makers – was created in 1903 to strengthen industrial ties.

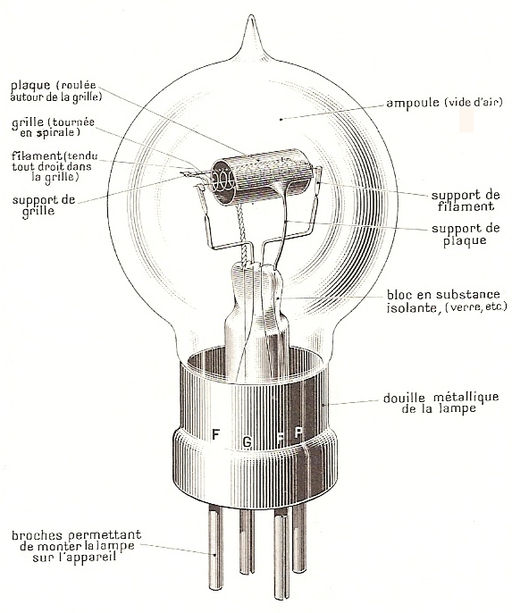

However, the cartel was rendered redundant in 1906 when two European firms invented a superior lightbulb with a tungsten filament. A few years later, two inventions by General Electric eclipsed this lightbulb: the metal-filament lamp with pure tungsten wire in 1911 and the gas-filled tungsten bulb in 1913.

The latter was commonly known as the half-watt bulb, and it contained argon or other noble gas that helped to preserve the tungsten in a better way compared to a pure vacuum. General Electric’s gas-filled tungsten bulb produced more light per watt (five times) than the previous carbon filament lamp.

General Electric’s licensing of its lightbulb patents resulted in more alliances, with the notable one being the mighty Patentgemeinschaft (“patent pool”) that took control of GE’s patent rights in Europe until First World War.

The patent pool disintegrated with the geopolitical reshuffling of World War I.

After the war crisis subsided and lightbulb businesses began sprouting again, a brand alliance – the Internationale Glühlampen Preisvereinigung- rose to control the pricing in a more significant part of continental Europe.

None of these alliances, though, had the ambition and impact equivalent to that of Phoebus.

The Contents of Cartel’s Agreement Document

On paper, the cartel sounded purely benign. Before joining the cartel, companies had to sign a document known as “Convention for the Development and Progress of the International Incandescent Electric Lamp Industry.”

This document listed the cartel’s main goals as to:

- Enhance the cooperation of all involved parties to the organization’s agreement

- Ensure that companies exploited their manufacturing abilities in bulb production

- Ensure and maintain high-quality lightbulbs

- Improve the effectiveness of electric lighting

- Increase light use to the consumer’s advantage

The Other Members of the Phoebus Cartel

Phoebus covered all lightbulbs used for medical purposes, heating, and illumination. Other than the four companies mentioned earlier, the cartel’s members included Tungsram (Hungary), Associated Electrical Industries (the United Kingdom), and Tokyo Electric (Japan).

Interestingly, the U.S.-based company, General Electric, one of the primary movers behind the cartel’s formation, was itself a non-member. Instead, it had several of its subsidiaries represent it, including International General Electric (British subsidiary) as well as the Overseas Group that comprised of its subsidiaries in China, Mexico, and Brazil.

To oversee various national bulb markets and their role in worldwide trade, Phoebus created a supervisory body, which Meinhardt of Osram chaired.

The other activities of the cartel were the facilitation of the exchange of technical know-how and patents and the imposition of long-lived and far-reaching standards. Today, consumers use the screw-type socket that Thomas Edison devised in 1880 and was designated E26/E27 by the Phoebus.

Astronomically High Sales

While the engineers of the cartel should have created a lightbulb that was long-lived and bright, it would have hindered the ambition of the members to sell more bulbs.

Initially, they sold more bulbs. During the 1926-27 fiscal year, the cartel managed to sell 335.7 million bulbs globally. Four years down the line, the sales increased to 420.8 million.

Despite a fall in manufacturing costs, Phoebus maintained almost stable prices and thus, higher profits.

The Beginning of the End for Phoebus Cartel

The cartel started struggling six years after its inception. Even in spite of the overall growth in the lightbulb market, sales volume declined by over twenty percent between 1930 and 1933.

The expiration of General Electric’s basic lightbulb patents weakened the cartel. The patents expired in 1929, 1930, and 1933, fuelled by occasional wrangles among the cartel’s members along with legal attacks, especially in the United States.

What finally killed Phoebus, though, was the World War II. The host countries of the cartel’s members went to war, making close coordination difficult. The 1924 agreement of the cartel that was meant to last until 1955 became null and void in 1940.

How the Phoebus Cartel Casts a Shadow in Today’s Lighting Industry

Although long gone, the impact of the Phoebus cartel can still be felt today. The lighting industry is going through one of the moment defining moments of technology transformation since the creation of the incandescent bulb.

After over a century of use, these bulbs are being replaced by LED and compact fluorescence lamps. End users are expected to pay more for lightbulbs that are up to ten times more efficient and have a lifespan of up to 50,000 hours, particularly for the LED bulbs.

Whether these pricier light bulbs will last as claimed, is a question that consumers are likely to investigate. However, reports have already shown that LED lamps and CFLs are burning out long before the indicated lifetimes.

Such incidents depict nothing less than careless manufacturing. There’s, however, no denying that these technologically advanced bulbs provide tempting opportunities to manufacturers to create life-shortening defects.

True, the twenty-first century lighting industry is far more driver and bigger than it was in the 19203 or even ’30s. Governments are more vigilant on collusive behavior too.

But the appeal for businesses to form alliances in such a market is even stronger. And the development of the Phoebus cartel shows such cooperation could succeed.