The estimated healthcare worker shortage projection:

short 18 million by 2030.

- The world continues to vary in its measures (see Shanghai, Apr 2022) to contain the covid-19 virus and simultaneously, fear.

- One out of eight nurses works in a country outside of their home country. In the United States of America, with a population of 331,002,647 as of 2020, has a total expenditure on healthcare per capita of $9,403 (2014).

- According to the most recent World Health Organization nursing report, investment in education, jobs and leadership are part of key action steps in creating a workforce of nurses.

- Many nurses holding faculty positions have inadequate clinical experience. The lack of clinically qualified faculty to teach in both undergraduate and graduate programs has been a serious problem in nursing institutions (Lu, 2004; Turale, Ito, & Nakao, 2008).

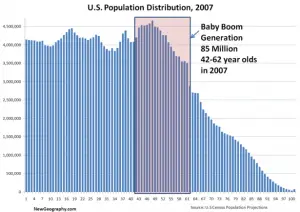

- Ultimately, with the baby boomer generation reaching a critical mass in line with the life expectancy at birth of 78.5 years as of 2019, a shortage of 18,000,000 nursing personnel seems to be pretty relevant.

Introduction & A Nurse’s Choice

In the third year of our global pandemic, one wonders where the next nurse is going to come from. Who will be taking care of us,

our loved ones,

or someone who’s going to change the future?

When one looks into the varying strategization methodology of governmental agencies worldwide, the measures represent a level of intricacy that, if applied correctly to the state of the shortage of across both hemispheres, there would be no shortage.

Through cross-referencing (1) the state of aging baby boomers, (2) average life expectancy in the United States of America, and (3) the ratio of nurses to other medical practitioners in their respective projected retirement dates, this writer sees a story in the choice presented to a young man or woman, growing up rurally: to survive in whatever mode/path available to them or to go into medicine and the care of our people and communities.

The English Barrier of Entry

Language barriers that may lead to errors may hinder the delivery of appropriate healthcare services and even result in life-threatening consequences for patients. For example, when a diabetic patient’s diet order has been written as “sugar free,” a non-English speaking nurse may interpret this to mean the “free use of sugar.” Such an interpretation could result in the patient experiencing a dangerously high level of sugar in the blood.

Increased migration of nurses to other countries, increased international travel, and the increased mobility of global epidemics have made competency in English a necessity. In addition, nurses enrolled in CNS, NP, master’s, or doctoral programs rely mainly on English language textbooks and research databases to keep abreast of the growing international body of nursing knowledge.

Opportunities for career growth may be restricted for nurses with limited English-language proficiency. A greater emphasis on helping nursing students master the English language is needed. Nonetheless, with growing online learning resources and management systems for education, opportunities to train and send a nurse only realistically requires approximately 500 hours of nursing training for the first level of certification for live-in aid, and another 400 hours from zero English proficiency to a score of 4.0/9.0 on the International English Language Testing System (IELTS).

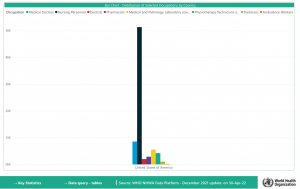

Nurses Outnumber Every Other Medical Personnel Category…And They’re Getting Old

With the very handy National Health Workforce Accounts Data Portal, seen in the large black bar, exists a 5:1 ratio in the number of nurses compared to medical doctors, nursing personnel, dentists, pharmacists, medical and Pathology Laboratory scientists, Physiotherapy Technicians and assistants, dietitians, and ambulance workers.

They outnumber every other medical professional. Five to one.

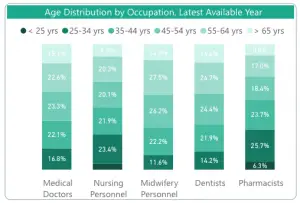

The data depicts a clear majority in the medical and hospital systems in each and every country. Not only that, the baby boomer generation needs care. And, as they age, the nursing workforce gets older with them. The most experienced, knowledgeable advanced nursing practitioners are aging out of our medical care systems.

Why not focus on the biggest group that cleans bedpans, makes sure people get their meds, and makes sure every infrastructural duties is fulfilled?

The Nursing Industry Overview

Differentiation in nursing practice based upon levels of education, experience, and competency helps to define the structure and roles of professional nurses (AACN, 1995). Differentiation criteria will continue to be established as the healthcare system demands higher levels of abilities and competencies from nurses. Future career pathways for nurses will occur as nurses more clearly define their identity, increase their skills, and adapt to new work environments. Nurses have always been a resilient group, able to respond to challenges proactively, to create new and exciting opportunities.

Greater emphasis on providing culturally competent care is needed to ensure that nurses are prepared to work in a multicultural world. Although the number of foreign workers, including professional and technical personnel as well as labor and unskilled workers, nurses remain ill prepared to offer culturally competent care to patients from different cultural and ethnic backgrounds. The nursing curricula in each of these countries provides only limited, if any, culturally specific content to guide nurses in caring for patients from cultures different from their own. Nurses’ overlooking of cultural implications of care can result in patients experiencing misunderstanding, mistreatment, or marginalization, all of which can impede their recovery.

Although the goal of a stable nursing workforce remains elusive. As the debate continues whether multiple entry points for nursing education and licensing is compatible with today’s healthcare needs, more employers are showing a preference for BSN-prepared nurses. As universities expand nursing programs and increase the number and quality of nursing graduates, the BSN degree is a standard.

The rapid expansion of APN, master’s, and doctoral nursing programs in each country. Such programs benefit the nursing profession by increasing the supply of advanced nursing specialists and faculty, generating research-related activity, and equipping nurses with higher levels of clinical expertise and leadership skills.

Career Development Opportunities

Each young lady or potential nursing candidate in SE Asia with very limited funds and education may choose amongst a wide range of entry-level jobs. While progression along these career development paths has potential, certifications and career pathways are significantly more accurately defined in nursing. A person could essentially train for 500 hours and learn English to gain employment as a live-in caregiver, returning in two years with approximately $70,000. During their employment, a nurse could engage in additional certification programs and research, combined with obtaining either their bachelor’s or master’s degree in nursing (online and clinically). A potential candidate pool of 1,000 fresh trainees could, within eight years’ time, net ONE advanced nursing practitioner (APN).

Unfortunately, eight years is exactly the timeline projected by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Types of Nurses

Certified Nurse Assistant (CNA).

Median annual salary (2020)1: $30,830

Projected employment growth (2020–2030)1: 8%

Licensed practical nurse (LPN).

Median annual salary (2020): $48,820

Projected employment growth (2020–2030)1: 9%

Registered nurse (RN).

Median annual salary (2020): $75,330

Projected employment growth (2020–2030)1: 9%

Advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs).

Median annual salary (2020): $117,670-117,670

Projected employment growth (2020-2030)1: 45%

Caregiver | Home Health Aide (HHA) | First Aid and Emergency Care | Hospice, Palliative, And End-Of-Life Care

Median annual salary (2022): $23,238-$36,560

Barriers of Entry and Circumstance

Due to a lack of physicians, there is a crucial need for advanced practice nurses to work in primary care settings, especially those located in the rural parts of the country. Nurses in rural practice must face many challenges, such as geographical isolation and limited resources which make it difficult to attract nursing professionals to work in rural healthcare delivery (Chin Limprasert, n.d.).

Additionally, nursing programs in these countries depend too heavily on the use of non-nursing clinical faculty who teach nursing content from a non-nursing perspective. Students may be taught, both in the classroom and in the clinical setting, from a biomedical standpoint, rather than from a nursing perspective. The use of physicians to teach undergraduate and graduate nursing courses is still common today, especially in Japan and Taiwan. Many teaching hospitals and universities prefer that physicians teach nursing courses due to their perceived greater technical and clinical expertise. A shortage of qualified nursing faculty results in this continued reliance on physicians to teach in nursing programs. Qualified nursing faculty are needed to develop and guide nursing students to fulfill their role as professional nurses, thereby empowering nurses with greater autonomy and control over nursing practice.

Abridged WHO Nursing Report

Nurses are critical to deliver on the promise of “leaving no one behind” and the global effort to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). They make a central contribution to national and global targets related to a range of health priorities, including universal health coverage, mental health and noncommunicable diseases, emergency preparedness and response, patient safety, and the delivery of integrated, people-centered care.

The nursing workforce is expanding in size and professional scope. However, the expansion is not equitable, is insufficient to meet rising demand, and is leaving some populations behind.

191 countries provided data for this report, an all-time high and a 53% increase compared to 2018 data availability. Around 80% of countries reported on 15 indicators or more. However, there are significant gaps in data on education capacity, financing, salary and wages, and health labor market flows. This impedes the ability to conduct health labor market analyses that will inform nursing workforce policy and investment decisions.

The global nursing workforce is 27.9 million, of which 19.3 million are professional nurses. This indicates an increase of 4.7 million in the total stock over the period 2013–2018, and confirms that nursing is the largest occupational group in the health sector, accounting for approximately 59% of the health professions. The 27.9 million nursing personnel include 19.3 million (69%) professional nurses, 6.0 million (22%) associate professional nurses and 2.6 million (9%) who are not classified either way.

The world does not have a global nursing workforce commensurate with the universal health coverage and SDG targets. Over 80% of the world’s nurses are found in countries that account for half of the world’s population. The global shortage of nurses, estimated to be 6.6 million in 2016, had decreased slightly to 5.9 million nurses in 2018. An estimated 5.3 million (89%) of that shortage is concentrated in low- and lower middle-income countries, where the growth in the number of nurses is barely keeping pace with population growth, improving only marginally the nurse-to-population density levels.

Aging health workforce patterns in some regions threaten the stability of the nursing stock. Globally, the nursing workforce is relatively young, but there are disparities across regions, with substantially older age structures in the American and European regions. Countries with lower numbers of early career nurses (aged under 35 years) as a proportion of those approaching retirement (aged 55 years and over) will have to increase graduate numbers and strengthen retention packages to maintain access to health services. Countries with a young nursing workforce should enhance their equitable distribution across the country.

Relative proportions of nurses aged over 55 years and below 35 years (selected countries)

Percentage of nurses less than 35 years

Percentage of nurses aged 55+ years

18 countries at risk of an aging workforceThe majority of countries (152 out of 157 responding; 97%) reported that the minimum duration for nurse education is a three-year program.

A large majority of countries reported standards for education content and duration (91%), accreditation mechanisms (89%), national standards for faculty qualifications (77%) and inter-professional education (67%).

However, less is known about the effectiveness of these policies and mechanisms. Further, there is still considerable variety in the minimum education and training levels of nurses, alongside capacity constraints such as faculty shortages, infrastructure limitations and the availability of clinical placement sites. The duration of nursing education is predominantly three or four years globally. A total of 78 countries (53% of those providing a response) reported having advanced practice roles for nurses. There is strong evidence that advanced practice nurses can increase access to primary health care in rural communities and address disparities in access to care for vulnerable populations in urban settings. Nurses at all levels, when enabled and supported to work to the full scope of their education and training, can provide effective primary and preventive health care, amongst many other health services that are instrumental to achieving universal health coverage.

One nurse out of every eight practices in a country other than the one where they were born or trained. The international mobility of the nursing workforce is increasing. While the patterns are evolving, equitable distribution and retention of nurses is a near-universal challenge.

1. Countries should strengthen capacity for health workforce data collection, analysis and use.

Actions required include accelerating the implementation of National Health Workforce Accounts and using the data for health labor market analyses to guide policy development and investment decisions.

2. Collation of nursing data will require participation across government bodies, as well as engagement of key stakeholders such as the regulatory councils, nursing education institutions, health service providers and professional associations.

3. Nurse mobility and migration must be effectively monitored and responsibly and ethically managed.

Actions needed include reinforcement of the implementation of the WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel by countries, recruiters and international stakeholders.

Partnerships and collaboration with regulatory bodies, health workforce information systems, employers, government ministries and other stakeholders can improve the ability to monitor, govern and regulate international nurse mobility.

3. Countries that are over reliant on migrant nurses should aim towards greater self-sufficiency by investing more in domestic production of nurses.

4. Countries experiencing excessive losses of their nursing workforce through out-migration should consider mitigating measures and retention packages, such as improving salaries (and pay equity) and working conditions, creating professional development opportunities, and allowing nurses to work to their full scope of education and training.

5. Nurse education and training programs must graduate nurses who drive progress in primary health care and universal health coverage. Actions include investment in nursing faculty, availability of clinical placement sites and accessibility of programs offered to attract a diverse student body.

6. Nursing should emerge as a career choice grounded in science, technology, teamwork and health equity. Government chief nurses and other national stakeholders can lead national dialogue on the appropriate entry-level and specialization programs for nurses to ensure there is adequate supply to meet health system demand for graduates.

7. Curricula must be aligned with national health priorities as well as emerging global issues to prepare nurses to work effectively in inter-professional teams and maximize graduate competencies in health technology.

8. Nursing leadership and governance is critical to nursing workforce strengthening. Actions include establishing and supporting the role of a senior nurse in the government responsible for strengthening the national nursing workforce and contributing to health policy decisions.

9. Government chief nurses should drive efforts to strengthen nursing workforce data and lead policy dialogue that results in evidenced-based decision-making on investment in the nursing workforce. Leadership programs should be in place or organized to nurture leadership development in young nurses. Fragile and conflict-affected settings will typically require a particular focus in order to (re)build the institutional foundations and individual capacity for effective nursing workforce governance and stewardship.

10. Planners and regulators should optimize the contributions of nursing practice. Actions include ensuring that nurses in primary health care teams are working to their full scope of practice. Effective nurse-led models of care should be expanded when appropriate to meet population health needs and improve access to primary health care, including a growing demand related to noncommunicable diseases and the integration of health and social care.

11. Workplace policies must address the issues known to impact nurse retention in practice settings; this includes the support required for nurse-led models of care and advanced practice roles, leveraging opportunities arising from digital health technology and taking into account aging patterns within the nursing workforce.

12. Policy-makers, employers and regulators should coordinate actions in support of decent work. Countries must provide an enabling environment for nursing practice to improve attraction, deployment, retention and motivation of the nursing workforce. Adequate staffing levels and workplace and occupational health and safety must be prioritized and enforced, with special efforts paid to nurses operating in fragile, conflict-affected and vulnerable settings.

13. Remuneration should be fair and adequate to attract, retain and motivate nurses.

14. Further, countries should prioritize and enforce policies to address and respond to sexual harassment, violence and discrimination within nursing. [And, with Zoom surveillance measures with IOT.]

15. Countries should deliberately plan for gender-sensitive nursing workforce policies. Actions include implementing an equitable and gender-neutral system of remuneration among health workers, and ensuring that policies and laws addressing the gender pay gap apply to the private sector as well. Gender considerations should inform nursing policies across the education, practice, regulatory and leadership functions, taking account of the fact that the nursing workforce is still predominantly female.

16. Policy considerations should include enabling work environments for women, for example through flexible and manageable working hours that accommodate the changing needs of nurses as women, and gender-transformative leadership development opportunities for women in the nursing workforce.

17. National governments, with support where relevant from their domestic and international partners, should catalyse and lead an acceleration of efforts to: build leadership, stewardship and management capacity for the nursing workforce to advance the relevant education, health, employment and gender agendas; optimize return on current investments in nursing through adoption of required policy options in education, decent work, fair remuneration, deployment, practice, productivity, regulation and retention of the nursing workforce; accelerate and sustain additional investment in nursing education, skills and jobs.

Actions include intersectoral dialogue led by ministries of health and government chief nurses, and engaging other relevant ministries (such as education, immigration, finance, labor) and stakeholders from the public and private sectors.

Investment in Education, Jobs and Leadership

A key element is to strengthen capacity for effective public policy stewardship so that private sector investments, educational capacity and nurses’ roles in health service provision can be optimized and aligned to public policy goals.

Professional nursing associations, education institutions and educators, nursing regulatory bodies and unions, nursing student and youth groups, grass-roots groups, and global campaigns are valuable contributors to strengthening the role of nursing in care teams working to achieve the population’s health priorities.

The investments required will necessitate additional financial resources. If these are made available, the returns for societies and economies can be measured in terms of improved health outcomes for billions of people, creation of millions of qualified employment opportunities, particularly for women and young people, and enhanced global health security. The case for investing in nursing education, jobs and leadership is clear: relevant stakeholders must commit to action.

World Health Organization (WHO)

Conclusion

Let’s train, send, and protect nurses.

18 million to go. 8.75 years.

A ton are retiring.